Preface

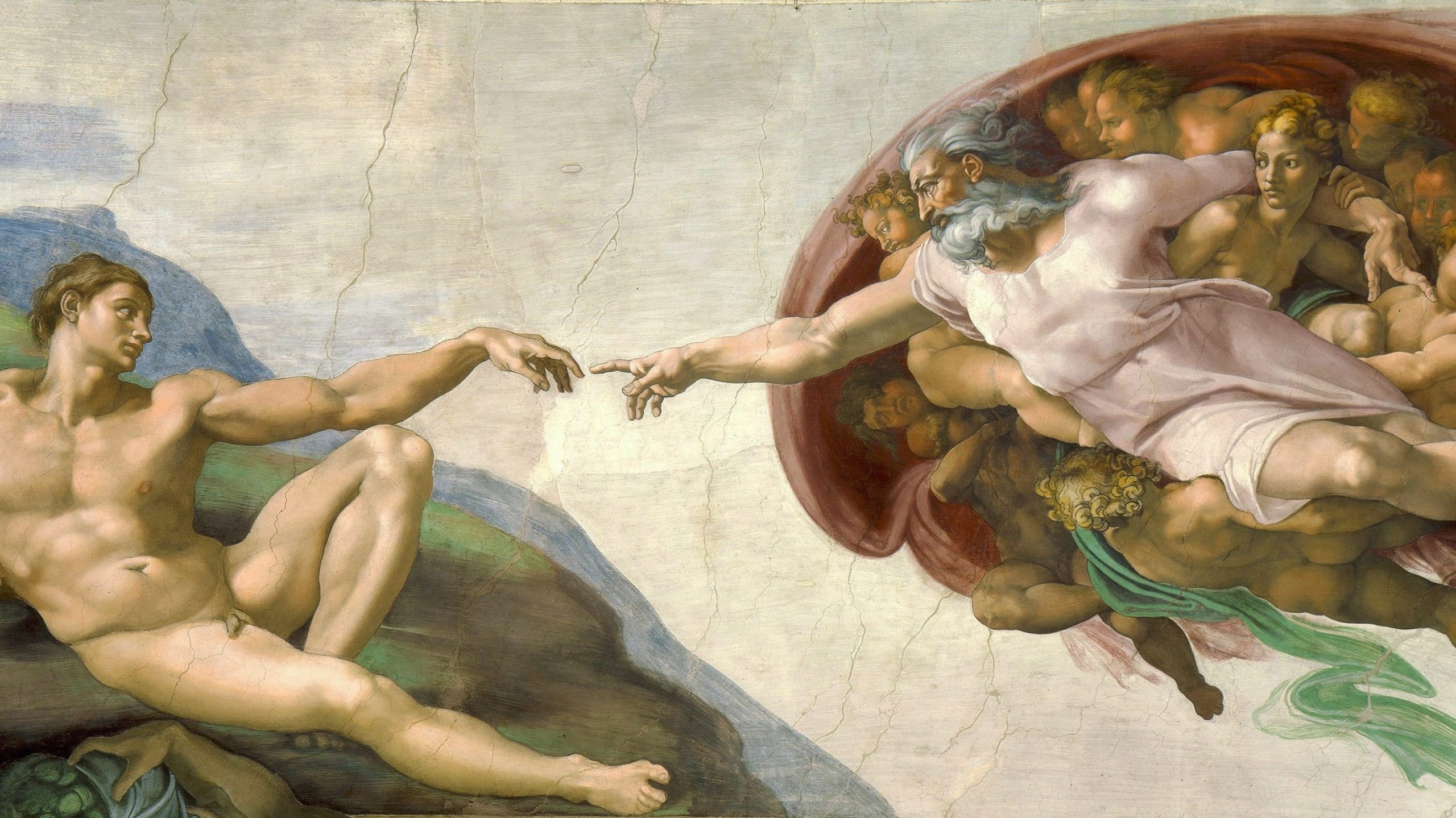

The image above, The Creation of Adam, depicts God bestowing consciousness. Look closely at God – notice that He, His cloak, and the others with Him form a human brain? This is an artistic demonstration of what most theists believe it means to be “made in God’s image”: to have a mind. To be capable of abstract awareness, and, by extension, to be able to know God.

What is consciousness? What’s the big deal? Consciousness is a combination of the ability to experience and the ability to self-reflect. Many will address what’s called “the easy problem of consciousness” – determining the processes related to different states – and move on. This neuron activates pain, this chemical causes pleasure, and so on. No problem, we’ve explained it! However, this mechanistic interaction does not explain why the result is a subjective experience of “feeling like” something – why is a particular series of electrical signals, pain? Why does it feel like pain, and not something else? Why does a certain frequency visually manifest redness? This is called the “hard problem” of consciousness – why biological creatures, instead of operating “in the dark” like computers, are animated. Whatever the solution may be, it seems to evade scientific, naturalistic explanation. It seems that something transcendental is going on here.

Lest anyone accuse me of crackpottery, allow me to cite a few prominent thinkers (more here). Steven A. Pinker, experimental psychologist at Harvard University, on how consciousness might arise from something physical, such as the brain, states, “Beats the heck out of me. I have some prejudices, but no idea of how to begin to look for a defensible answer. And neither does anyone else.” Donald D. Hoffman, cognitive scientist at University of California, Irvine: “The scientific study of consciousness is in the embarrassing position of having no scientific theory of consciousness.” Stuart A. Kauffman, theoretical biologist and complex-systems researcher: “Nobody has the faintest idea what consciousness is… I don’t have any idea. Nor does anybody else, including the philosophers of mind.” Eugene P. Wigner, Nobelist in physics: “We have at present not even the vaguest idea how to connect the physio-chemical processes with the state of mind.”

There are three mysteries related to the hard problem of consciousness: qualia, psychophysical harmony, and intellect. Unlike something such as the contingency argument, the argument from consciousness is not a formal, deductive proof of God’s existence, but an inference to the best explanation given the available evidence; nonetheless, it is a strong, intuitive argument, and these three aspects together form a compelling case for theism.

YouTube video of this argument here.

Qualia

“Qualia” is the word for subjective qualitative states; essentially, the “what-it’s-like-ness” of a thing. An easy way to determine whether something is a quale is if it cannot be objectively described. For example, try to think of how you would describe red to someone who was born blind. There is no objective answer; you can only describe a color by referring to another color. Or, imagine what it’s like to be a bat. You might imagine yourself hanging upside down or flying around, but this is precisely the issue – you’re imagining yourself doing these things, because you have no point of reference by which to understand the true inner life of a bat.

If qualia are subjective, it’s difficult to see how naturalism could explain them in principle. Imagine we built a robot that was designed to run through the woods. It would need an unbelievably complex array of sensors which provide a map of the world around it. It would need the ability to navigate through auditory, visual, and tactile sensors. Let’s say we built this computer to perform this task just as well as most humans – would it then magically feel something while performing it? We have no reason to think it would. That is, the robot could operate through the use of these senses without actually experiencing anything. Consequently, there’s no reason to think evolution couldn’t have developed animals the same way. We could’ve just been flesh robots, performing evolutionary tasks just as well as we do now. Why aren’t we?

Even if one were to suggest that qualia have a positive effect on survival, there is still no way evolution could “create” qualitative experience. Evolution is only capable of acting upon a genome. There are no “experience organs” or “consciousness cells,” so there’s nothing for it to act upon. In other words, in an open system, evolution can bring creatures to higher levels of complexity, but it cannot explain the categorical shift from, “complex without subjective experience,” to “complex with subjective experience.” Why is the metaphysical status of our universe such that qualia emerge in complex carbon-based lifeforms? What sorcery could transform unfeeling, disparate material into a unified center of subjective experience?

We might appeal to multiple solutions for this problem: panpsychism (consciousness is a property of matter), pantheism (God is the universe), panentheism (God is transcendent but the universe is part of Him), or theism (a God who is a totally transcendent designer). Though this should move one away from naturalism, this hasn’t gotten us all the way to theism. How do we bridge the gap?

Psychophysical Harmony

Consciousness begins to point to theism distinctly through something called psychophysical harmony. Psychophysical states describe the relationship between subjective, “psychic” states (qualia) and objective, physical states. We know from experience that these are in harmony in our universe – for example, when something objectively physically bad happens, like breaking an arm, we experience pain, and when something objectively physically good happens, like going to sleep after a long day at work, we experience pleasure. But Dr. Dustin Crummett argues that this harmony between qualia and physical reality is not a foregone conclusion. In fact, there are only five ways this relationship could be configured, and as we will discuss, we would not expect harmony under any of them a priori, and each of the five would ultimately require theism to explain harmony.

Possibility #1: The psychic does not affect the physical, and vice versa.

The idea here is that your body physically functions, and your qualitative experience exists entirely separate from that function. However, if subjective experience is not at all affected by physical inputs, then their correspondence to mental states doesn’t make sense. In the real world, two people can look at a tree and both agree that it’s a tree and actually experience looking at a tree. But if our psychic states are totally disconnected from our physical states, why is that the case? Our bodies are just running on “autopilot” anyway under this paradigm. Why don’t we subjectively see random images and hear random noises while our bodies agree that it’s a tree? Or just see and hear gray static all the time, for that matter?

Possibility #2: The physical does affect the psychic, but not the other way around.

The idea here is that your body handles all of its functions “on its own,” and your subjective experience is just “along for the ride.” This would explain why our subjective experience is connected to reality, but not why it is meaningfully connected to reality. Under this view, your physical experience could affect your conscious experience in totally incoherent ways. What’s the difference? Your body “decides” what it’s doing on its own; the qualia are unimportant. So, for example, imagine two people look at a tree. One may see a slightly different tint of gray than usual, and experience unbearable pain. The other might experience a red glare and desire. But in neither case could qualia encourage them to stop looking at the tree, because psychic states have no impact on our physical states.

Possibility #3: The psychic does affect the physical, but not the other way around.

This is the most absurd possibility. On one hand, it fails to explain why qualitative states seem to reflect physical reality in a coherent manner. On the other hand, it also contends that this subjective experience can somehow cause changes in a material brain it has no receptive connection to. The result of this would probably be the experience of gray static with some sort of random physical writhing.

Possibility #4: The psychic and the physical interact with each other.

Based on our experience of consciousness, this is certainly the most likely thus far. However, pointing out the mutual relationship still does nothing to explain how and why these states interact uniformly. We could have incoherent interactionism, for example, like qualia inversions. That is, we could randomly experience pain during some objectively physically good activities, or pleasure during objectively bad ones. Here’s an example: you see expired milk in your refrigerator. Your body is revolted, but you subjectively experience this stimulus as the quale of pleasure. You drink the milk because of this. Then your body throws up because the milk is rancid.

Natural selection is often cited as a response to this, since harmonious interaction would be advantageous. That is, organisms with the right calibration would thrive, and organisms with the wrong calibration would not. However, this argument presupposes the very uniform harmony or disharmony we’re trying to explain. Again, natural selection can only select a genome in accordance with the laws of nature; it can’t change the laws of nature. So if each organism experienced qualia with random inversions, there’d be nothing to naturally select. Even if the statistical improbability occurred in which an animal happened to have the “right” set of qualia, there’s no reason under this paradigm to think the harmony would be genetically transmissible, nor even that it would last for more than half a second. Every individual being could have different sets of psychophysical states at different times. No solution.

Possibility #5: The mental state is entirely corporeal, so there is no interaction between psychic and physical; it’s all physical.

There are two forms of physicalism; the first is the a priori physicalist. This is the position that all psychophysical truths can be deduced from the physical world. In other words, we can explain qualitative experience as a physical truth the same way we can deduce that a Euclidean triangle must be 180°. But obviously, this raises multiple issues. For example, it would mean we actually can know what it’s like to be a bat, and that we can explain red to the blind, and this seems absurd. Further, it would have to be impossible to conceive of qualia inversions, the same way it is impossible to conceive of a 190° triangle. This is evidently not the case, considering the past few examples coherently described qualia inversions. There are practically no philosophers or scientists of mind who hold this view, so we’re going to ignore it.

The other option is a posteriori physicalism, and this view contends that physical and mental states are equivalent to each other, but can only be known through experience. Or, in other words, qualitative states are not a logical necessity like the degrees of the Euclidean triangle – it is conceptually possible they could’ve been different. The a posteriori physicalist can conceive of possible worlds where qualia are inverted. They just contend that’s not the one we happen to live in. In this particular world we inhabit, it is a metaphysical necessity that qualia are harmonious with sense, the same way the gravitational constant and the speed of light just are what they are, even though they might not have been. That is a satisfying answer for this world. But then we have to ask the question – how many possible worlds are there where it could’ve been different?

The classic “fine tuning for life” argument tends not to be very compelling due to observer bias. Of course the universe appears fine-tuned for life; how would life be there to observe it if it wasn’t? But this argument doesn’t have the problem of observer bias. There are trillions of possible worlds where we could have existed as living observers with our qualitative experiences in disharmony with physical reality. What are the odds we happen to be in a world where there is perfect harmony?

Much like the last example, natural selection is often the response to why our world is so ordered. But much like the last example, this just doesn’t answer the question. If an organism exhibits the behaviors and dispositions consistent with the avoidance of drinking spoiled milk without any phenomenal experience of nausea, it is in no way evolutionarily advantageous to have the phenomenal experience of nausea. Likewise, if the phenomenal experience inverted such that spoiled milk causes pleasure it still wouldn’t make a difference, since evolution can simply invert the response and select for pleasure to result in avoidance behavior. You would be safe from the rancid milk and evolution would be happy, but your subjective experience would be a nightmare where you always feel pleasure when exposed to spoiled food and drink. Psychophysical harmony is prior to natural selection, and for physicalists natural selection is indifferent to it.

Solutions

So, which solutions might be consistent with psychophysical harmony? One might raise five options: luck, panpsychism, pantheism, panentheism, or theism. Luck is untenable, since we would be against functionally infinite odds. Panpsychism would explain qualia, but does not explain psychophysical harmony. Pantheism and panentheism fail, because a God whose identity includes the universe could not explain its metaphysical configuration any better than the universe could to begin with. Theism thus provides the only satisfying solution: a transcendent, logical designer. While we would not expect psychophysical harmony a priori, we would expect a designer to design logically a priori, since logic is invariant, universal, and self-evident; just as A<A+1 is true in all possible worlds, psychophysical harmony makes logical sense in all possible worlds, so its instantiation is sufficiently and exclusively explained by a designer who would understand this fact.

Intellect

Finally, we will explore the intellect, a faculty which, I will argue, suggests God has a special predilection for mankind. I will be employing two terms here which are often used differently, so I must begin by defining them. First: “cognitive.” Cognition is the process beginning with what the “5 senses” perceive in the environment. The common sense faculty unites this information into a coherent percept. This percept forms a picture in the imagination, which the memory retains. This all contributes to the “estimative power,” or instinctive value judgment. You can meditate on this process from start-to-finish using the infamous example of “Pavlov’s dogs.” The dogs sense the bells and the food, the common sense faculty presents this experience as a concrete percept, the brain receives and stores this mental impression of bells and food coming together, informing the estimative power to anticipate food and salivate when a bell rings.

Second, “intellect.” While the cognitive process receives, imagines, stores, and responds to material sense information, the intellect sees beyond materiality. In man, these processes are synergistic; we receive through the senses, yet we can see beyond them. For example, Chopin’s Nocturne op. 9 no. 2, Van Gogh’s Starry Night, and Percy Shelley’s Ozymandias have absolutely nothing in common from a sensory perspective, and none would have any great effect on a monkey, yet each of these demonstrate beauty to the human mind. Intellect is the ability to understand abstract concepts (such as beauty) and to reason. It is the fullness of consciousness. Bear in mind that in the research I’m citing, they may use these words differently.

Here are my two key points: first, animals with similar cognitive ability to humans are incapable of abstraction. This points to the idea that intellect, though synergistic with cognition, is not a higher form of cognition, but a categorically separate, emergent property totally unique to mankind in the known material world. Second, there’s no plausible naturalistic explanation for intellect given that it definitionally performs a nonphysical activity. These points suggest that mankind’s intellectual nature is a special endowment, not a random cosmic occurrence.

Point #1A: Confronting bias.

If you google, “can animals abstract?” you’ll find dozens of articles about how they can. Here’s one from Scientific American titled, “Many Animals Can Think Abstractly.” The evidence for this claim is a few apes who, after hundreds of trials, succeeded in associating images of similar animals “better than chance.” Hm. Well, here’s an article titled, “Insects Master Abstract Concepts.” It refers to a study in which bees figured out that one configuration of images leads to a reward, and the other to punishment… after 30 consecutive tries, using the same configuration every time. Here’s one called, “Dogs Can ‘Think Back’ and Form Abstract Concepts.” The researchers are astonished to learn that dogs can be trained to do things again when told, “again.” This so startles one researcher that he says, “we’re learning that humans aren’t that cognitively unique after all.” These dogs are on the verge of special relativity.

Now, I’m not saying that all studies into animal abstraction are lazy and biased. I am only pointing out that pop science has reached a verdict on animal consciousness that real science has not. I think the reason for this is that people like the idea of their pets being just a little more aware than they seem. Koko the gorilla is a great example. Koko was famous for being the first gorilla to “speak sign language.” Her seeming consciousness and heartwarming sentimentality for humans took her and her trainer to stardom. Her trainer, Penny Patterson, constantly put out PR about Koko’s consciousness, despite never performing a single controlled experiment to prove it. Koko never made any spontaneous signs, and nearly every string of signs she ever made was gibberish. But people wanted it to be true, so it worked.

As cool as it would be, the real research suggests Fluffy the dog’s subjective experience is probably nothing like yours after all.

Point #1B: There are many reasons to think animals do not have intellect.

There are all sorts of animal activities that we label as “abstract” which are absolutely not. For example, monkeys are capable of putting triangular objects into triangle-shaped holes. This does not denote understanding of triangularity, rather just the capability to associate one physical object with another. Some animals can make pretty interesting associations, such as connecting an object to a stimulus via a shared stimulus. But this is still not abstraction, and this is the highest form of mental capability animals have ever shown. Even more plausibly abstract tasks like tool use are, believe it or not, still not evidence of abstraction. Humans with brain damage can maintain a full capability to abstract while being incapable of using tools, which proves tool use can be a physical process independent of abstract understanding.

When animals “teach,” it is purely adaptive. They instinctually behave in a fashion which rears their young to perform advantageous behaviors, but they are not aware of it. A cat may “teach” its young to hunt, but it is a matter of cat-specific natural selection. Humans, on the other hand, can apply practice and teaching to abstract ends as a general competence. No definitive examples of “planning” have been observed in lower animals, rather further demonstrations of inflexible adaptations. This includes the storage of food or migration of birds. Humans are, of course, capable of abstract, multi-step goal-setting.

The most developed animals have a form of cognition whereby a goal-directed act followed by a desired item creates association. This is a higher function than basic association, by which direct stimulus is related to a desired item. On the other hand, humans can develop a conceptual theory of causality. So, where a lower animal may form a goal-directed association with pressing a button in a lab setting and receiving a meal, a human would understand that there is no intrinsic causal connection between pressing a button and the presence of food, and would look for an intermediary explanation.

Short term memory in chimpanzees is equal to that of humans in terms of raw cognitive power. But consider the following sequence: 1492 1776 1865 1918 1945 1980 2001. A chimp would only be able to see an indiscriminate series of squiggles and perhaps be able to remember the first 8 or 9 of them. But a human can abstractly relate each number to the year of an event in American history. Thus, the human can practically reduce the dataset from 28 to 7, and then remember that order through the concept of chronological sequence.

Animals do show some basic propensity to deceive, but once again it has only been shown in relation to adaptive functions or by association. In the latter, despite hundreds of reinforcements, monkeys found the suppression necessary for a basic act of deception very difficult. Contrast this with humans, to whom acts of deception are a “domain-general competence which can serve many goals.”

“When [animals] find that A leads to a larger reward than B, B a larger reward than C, C a larger reward than D, D a larger reward than E, and are given a choice between A and E, they choose A.” In animals, this inference only exists when rewards are present, which drive the instinct to mechanically pursue the greatest reward. They show no comprehension of monotonic order as a concept. On the other hand, children (age 3) show the ability to order objects in a monotonic series, but also to develop their own monotonic metrics of evaluation. In other words, 3-year-old humans understand the concept of order; they do not mechanically infer.

“Animals neither attribute embedded mental states nor have embedded social behavior.” They are capable of understanding the perceptions of agents, but cannot ascribe a presence of knowledge or a state to the agent. In other words, they are capable of instinctual reaction to mechanical stimuli presented by other agents. On the other hand, human infants aged only six months are capable of distinguishing psychological objects and assigning positive or negative emotional states to them. I must point out that chimps of greater cognitive ability can do nothing of the sort.

The best research ever done on animal lingual abilities was the study of Nim Chimpsky, a chimpanzee raised as if it were a human and taught sign language to see if it would comprehend it. The unequivocal conclusion was that Nim could only learn sign language as a matter of perceptual association and memorization. On the other hand, young human children with similar cognitive ability understand abstract grammatical rules. Look at the three sentences you just read: there are 69 words, and only 8 of them have material referents. The other 61 words refer to abstract concepts a chimp would find fundamentally inaccessible, like trying to explain red to the blind.

Point #2: Evolution cannot explain intellect either way.

There is yet another issue for the proponent of a naturalistic development of consciousness: evolution can’t explain it.

Evolution acts upon a genome through the process of natural selection. In other words, it selects for material properties of organs. In this fascinating video, Richard Dawkins describes the process of the evolution of the eye. It begins with the most elementary and basic degree of sense, detecting presence or absence of light. Then it slowly mutates to perceive shade. Later, some animal has a blurred image, and then another a more precise image, and so on. There are two facets to this theory of the eye’s development which make it coherent. First, the development creates an advantage. Second, the development operates upon an organ by gradation.

Intellect clearly fulfills the requirement of being advantageous. Consider a tribe of neolithic hunters developing an abstract plan to hunt large game, for example. However, the second condition is what makes a theory of the natural development of intellect implausible. Teleportation would certainly confer an evolutionary advantage to humans, so why don’t we have that ability? Well, natural selection can’t develop it. Teleportation is not a process which could be contained by an organ or set of organs, and evolution only acts upon organs. Likewise, intellect is definitionally the ability to perceive something which doesn’t sensorily exist. The eyes do not and cannot see justice, truth, or beauty for example.

This isn’t a “God of the gaps” appeal to the fact that we just haven’t found a biological solution yet; it’s an observation that intellect is definitionally incompatible with evolution. How could the ability to comprehend what can’t be sensed by an organ be developed by an organ? Which organ could contain “abstraction?” The eyes? The amygdala? The prefrontal cortex? The hippocampus? Some mix of them? How could a mix of different sense-receiving and sense-processing organs see beyond the senses? Even though there are predictable neural correlates to abstraction, the correlates cannot actually explain this emergent property. Why, then, is this property which is conspicuously absent from the natural world, singularly present in mankind? Well, psychophysical harmony led us to infer that God exists and is the designer of qualitative experience; the most straightforward inference here, then, is that man simply has a singular place in God’s design.

Conclusion

You are made of about 100 trillion cells – none of them are conscious. None of them know who you are. Yet miraculously, 100 trillion cells stacked on top of each other form – you. A unified center of consciousness who loves, desires, dreams, thinks, and creates. Investigating the three key aspects of this reality – qualia, psychophysical harmony, and intellect – points to theism as the only reasonable explanation for this.

First, the existence of qualia. It is unclear how it would be possible in principle for an unconscious, mechanical universe to result in beings who experience subjective states. Second, psychophysical harmony. The uniform coherence of qualitative experience cannot be reasonably explained by anything but a logical, transcendent designer. Third, intellect. Abstraction – an emergent property which allows a creature to consider immaterial universals – is categorically different from cognition. It is impossible to imagine a material explanation, by nature of its definition as an extrasensory activity. These realities are consistent with the previously inferred designer bestowing this power singularly upon mankind.

Now let’s talk a little bit more about intellect. Following from Aristotle’s work, later thinkers argued that the intellect can survive physical death. Why do they think this? Because what the intellect does is understand immaterial, invariant universals like essence, logic, truth and so forth, and this function would not seem to inherently require a material body and abstraction. A nonphysical intellect might know truths innately, as all men understand cause and effect a priori, or one being might communicate knowledge directly to another without material mediation. Imagine, then, your intellectual consciousness as a fixed point of knowledge and experience. The material world is sort of like an interactive slideshow sequentially understood by that fixed point. But the fixed point does not require the slideshow. Eventually, when the slideshow ends, the theist may suggest that your consciousness will remain, experiencing one endless moment.

So, back to The Creation of Adam. Awareness of God first requires awareness – qualia, psychophysical harmony. But then it requires awareness of the immaterial, which is intellect. Indeed, wherever you stand on intellect, it is absolutely certain that humans are the only beings on earth who can comprehend the idea of God. And that’s the whole point of the painting. Perhaps consciousness is not an existential burden to distract ourselves from, but rather the privilege of being made in the image of God, the all-knowing, immaterial mind behind all creation? Perhaps consciousness is not just a strange accident in a vast, uncaring void, but an invitation from a friend to share an immobile instant of eternity?