The Basics

Existentialism is a belief system, not a religion, and it is the natural corollary to atheism or agnosticism. I must draw a distinction between genuine existentialism and existentialist thinkers. A genuine existentialist believes that no one is here “for” something, no one is required to do anything, and there is no “bigger purpose.” Life is what you make of it. Although Sartre’s “existence precedes essence” carries some implied philosophical baggage beyond this, I think it is a pithy description of this idea. Further, Sartre pontificates that “if existence precedes essence, God is meaningless.” Quite right. Existentialist thinkers, on the other hand, use existentialist ideas without actually believing that one doctrine. We will see one such example in Kierkegaard.

So, to reiterate, a true existentialist (per my definition) is simply someone who believes essence is not objective, but subjectively determined by an agent. This necessarily follows from atheism/agnosticism because if there is no higher mind which organized reality (into essences), there is no higher reality to respond to than our own determinations as conscious agents.

The denial of God, atheism, like any simple denial, is not a very interesting subject. What is a very vibrant subject is what to do once one has denied God. Existentialism covers a wide swath of ideas, but its core concern is that question.

History

There is no real consensus on what led to the enlightenment, or “age of reason.” But there are a few significant factors all agree upon. First, the Protestant Reformation ended the ubiquitous dogmatic authority of the Catholic Church. People were free to believe whatever they wanted about Christianity. Combined with the Renaissance, this birthed “humanism,” which focused man’s attention on man, as opposed to the divine. The scientific revolution led to the questioning of the Aristotelian metaphysics which had been accepted for centuries. All of this together resulted in philosophers questioning even the most basic assumptions about the human experience.

But regardless of the extremities of metaphysical questioning, enlightenment era philosophers still maintained their grip on rationalism. Despite rejecting Plato’s conclusions, Plato’s methods were still dogma. Descartes’ Meditations I begins by breaking down all human assumptions and “restarting” from I think, therefore I am. Kant points out the ostensibly infinite gap between objective reality (noumena) and human experience (phenomena). But both of them still used the classical framework to ultimately prove that God and objective reality exists. But the focus and the methods of enlightenment thinkers shifted with Søren Kierkegaard.

Søren Kierkegaard, born 1813, is considered the father of existentialism. He coined the word, “angst” in his book The Concept of Anxiety. His definition of angst is the experience of facing innumerable choices with almost no capacity to understand them. “Life can only be understood backwards, but must be lived forwards,” he said. In essence, Kierkegaard pointed out that man’s life was an internal paralysis about what to do next, leading to meaningless mimicry instead of exploration. “Life’s meaning” is to get a job, marry a high-society woman, agree with the majority opinion, and find salvation by casually admiring Christ and receiving Communion once a year. His primary gripe with society was its mindless mass production of human drones.

Under Kierkegaard’s paradigm, no institutionalized behavior could solve the problem of angst. But one thing, he thought, could – Christ. To Kierkegaard, the simple truths of the Gospel lived out in one’s life were the solution to the emptiness. Unlike his predecessors, he did not think that God could be found through rational argumentation, only that one’s need for God could be found through rational argumentation. And once one hits that point, there is only one thing to do: take a leap of faith (another term he coined). He rejected the rationalistic theistic efforts of Aristotle, Aquinas, or even Descartes. To him, “faith” was not an addendum to evidence, but a triumph over rationalism itself. “To have faith is to lose your mind, and to win God.”

Kierkegaard is of course more famous for his diagnosis than his medicine. I think the major innovation of his work was to stop looking at what we do and start looking at us. The idea took on a new shape in the post-Darwinian era, in which the intelligentsia generally turned away from the idea of God. Kierkegaard’s call to authenticity was one thing under his paradigm, but what does authenticity mean if there is no God? If it’s all up to you?

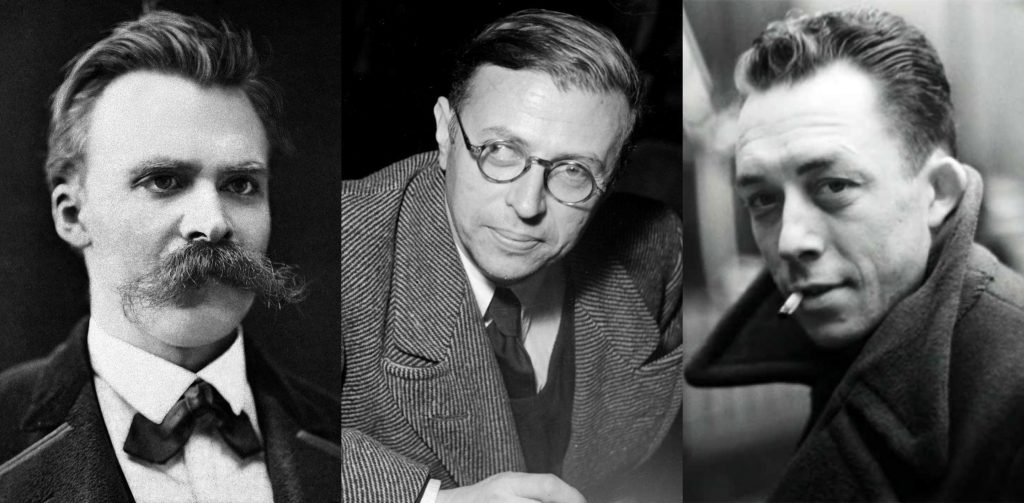

Nietzsche

“God is dead. And we have killed him. Yet his shadow still looms. How shall we comfort ourselves, the murderers of all murderers? What was holiest and mightiest of all that the world has yet owned has bled to death under our knives: who will wipe this blood off us? What water is there for us to clean ourselves; what festivals of atonement, what sacred games shall we have to invent? Is not the greatness of this deed too great for us? Must we ourselves not become gods simply to appear worthy of it?”

Nietzsche claimed that classical morality had been destroyed with the rejection of absolute authority. The paradigm of right and wrong was over, as he described in Beyond Good and Evil. His answer to the vacuum was that man must stop looking upward in order to find value and truth, and start looking inward. And what do we find when we look inward? A will to power. Even amoebas demonstrate “will to power” when one consumes another. It is the most fundamental of fundamentals. Nietzsche posits that Christianity appeals to people because it lets them pretend to have power in their weaknesses: “slave morality.” In other words, he taught that it is not because of morality that we refrain from certain behaviors; rather, we refrain from certain behaviors because we are too weak to engender them, and label that impotence “morality.”

Nietzsche’s most famous passage on slave morality and the transcendence of it comes from Thus Spoke Zarathustra, a satire of holy books. His idea is a metamorphosis. First, mankind is like a camel. The camel is unhappy with its burden, but impotent to relinquish it. Instead, it denies its true desires and calls them evil, glorifying its own ability to carry such weight instead. This is like the Christian who is desirous of promiscuous sex, but, unable to achieve it, condemns fornication and glorifies their own virginity. Then, says Nietzsche, mankind grows into a lion. The lion rejects the burdens imposed upon it with violent fury, and with success. But the lion is not at peace until it moves beyond the acceptance/rejection paradigm, finally becoming a child. The child sees the world with fresh eyes, free to create its own values, free to love its fate wherever it goes.

This “child” is what Nietzsche calls the Ubermensch, or “Overman.” It is important to note that this allegory does not apply to the personal growth of a particular person. The Ubermensch is literally a further evolution of mankind, a sort of existentialist Messianic figure. The camel represents mankind during the Christian epoch, glorifying slave morality. The lion is mankind from the enlightenment to the present day. Nietzsche called our epoch “a bridge” in which the best any of us can do is “pave the way” for the coming of the Ubermensch.

Nietzshce’s thoughts have been criticized for serving as an inspiration to the Third Reich. Notably, he never uses the word “untermensch,” the racist term used by the Nazis to refer to “lesser” people destined for extermination. Nor does he ever speak about what ought to be done regarding lesser people, those he dubbed “the last men.” Even further, he describes himself several times as an “anti-antisemite.” Though we can be absolutely certain that genocide was not his intent, it’s hard to avoid that the ideas of mankind’s transcendence of morality, commitment to the will to power, and the pseudo-religious theme of eugenic determinism seem perfectly compatible with the philosophical groundwork of the “Final Solution.”

Sartre

“Man is condemned to be free; because once thrown into the world, he is responsible for everything he does. It is up to you to give [life] a meaning.”

Sartre’s magnum opus, Being and Nothingness categorizes beings into two buckets – unconscious and conscious. An unconscious being’s identity is factual and determinate. That rock is that rock. This rock is this rock. But conscious beings are a different matter. He borrows from Husserl in pointing out that consciousness is inherently relational – that is, there is no such thing as “being conscious,” only “being conscious of something.” A rock simply is what it is, but a conscious being only exists as it relates to another thing. Consciousness itself is translucent, unidentifiable. You are presently conscious of my writing, but you are not my writing. Sartre calls this “nothingness” – read it as, “no thing-ness.”

Sartre believes that human “no thing-ness” means total lack of identity and thus, total freedom. However, Sartre points out that one pesky issue leads to all the trouble with ourselves: we are objects to others. Sartre pontificates on this using the infamous example of “the Look.” Imagine walking into a room, thinking you are alone, humming a silly song, and then spot someone sitting there. Their presence transforms your entire world. You become hyper-aware of yourself. You are no longer living in your own world, but in their world, with their values and assessments being applied to you without your consent. But imagine you look closer, and realize it was actually a mannequin. A sigh of relief. Instantly, the world instantly transforms back into your world. You are no longer an object.

Sartre says our relationship with the subjectivity of others leads to “bad faith,” Sartre’s idea of self-deception. Contrary to Freud and the psychoanalysts, Sartre contends that self-deception is necessarily conscious, not subconscious, and that we do it to keep our worlds intact. The example he gives is of a woman who goes out with a man for the first time. She enjoys his sexual infatuation, and in fact, she wouldn’t find him charming if he was only dispassionately interested in her. But she simultaneously pretends nothing of the sort is going on, so as to ignore that something is tacitly being asked of her. She creates a world in which he both is and is not sexually interested in her at the same time – bad faith.

The worst kind of bad faith is that which causes us to relate to ourselves as if we were objects. One relatable example is “the waiter.” A man, in order to absolve himself of responsibility for his own actions, instead chooses to define himself as a waiter. He moves from table to table a little too quickly; holds his tray a little too perfectly; smiles with just a little too much interest for the customer. He lifts the burden of self-actualization off of his shoulders by simply repeating the prescribed activities that waiters perform, as if he had no other choice. By “hiding” his own freedom from himself, he becomes something less than human, a mere part of the scenery.

In Sartre’s play No Exit, he explores the idea of this alienation through the story of three people stuck in a room. Each of them have a distinct idea of themselves, and each of them want the other two to view them as they view themselves. But all three have free will, and their own unique perspective. Despite clever argumentation, peacocking, and selective storytelling, they can never compel the others to view them as they view themselves. They realize they are in Hell, and that damnation is to have one’s ego invalidated by another conscious being. Towards the end, the door flies open; they all have the chance to escape, but the escape is into the unknown. They are too cowardly to take the opportunity, and close the door instead – a metaphor for rejecting freedom and clinging to bad faith instead.

To Sartre, the goal of existentialism is to accept total responsibility and act with authenticity. Authenticity is not acting with complete spontaneity, as if one were not under any conditions whatsoever. That would not be freedom, but bad faith – denying the reality of physical conditions. But authenticity is, of course, not assuming a static role and objectifying oneself either. Authenticity is a recognition and response to the interaction between facticity and freedom – being, and no thing-ness. “I wish, above all, to be conscious of myself as a thinking, willing, active being, bearing responsibility for my choices and able to explain them by references to my own ideas and purposes” (Berlin 1969, 131). Combined with his disbelief in objective moral values and advocation of value-creation, Sartre’s ideal is quite like Nietzsche’s Ubermensch.

Sartre was massively popular and wrote an enormous amount of content. Notably, Sartre was a vocal Marxist. To him, Marxism would make men more free by loosening some of the conditions imposed by society. Perhaps the waiter in his earlier example could become a traveling saxophone player if he didn’t have to worry so much about capitalistic endeavors. Sartre did not believe in objective moral values; he was fully supportive of the use of terror and violence to impose communism – the noble ends justify the means. He met with Che Guevara and Fidel Castro, and was the west’s most prominent Stalin apologist for decades.

Camus

“Should I kill myself, or have a cup of coffee?”

Albert Camus’ most profound entry to philosophical literature was his commentary on the ancient Greek myth of Sisyphus. If you are unfamiliar, Sisyphus was a swindler par excellence. Among his many exploits, he managed to trap death, leaving thousands whom death was supposed to claim awaiting him in unutterable agony. This was the final straw for Zeus, who condemned him to the worst punishment he could concoct: Sisyphus was placed in Hades with an irresistible compulsion to push an enormous boulder up a hill. But every time he pushes it up, it just rolls back down. Forever.

Camus notes that Sisyphus is not so different from us. Every day we wake up, shower, eat breakfast, go to work, eat some lunch, keep working, small talk, go home, sit on the couch, read a book or watch TV, go to sleep. We buy a house so we can live in it so we can work so we can have a house to live in. We have kids so they can endlessly repeat the cycle. But why? The fact of the matter is that we can spend all day justifying activities within life, but we can’t justify life. And if we can’t justify life, why do we bother with living? Camus suggests that we compulsively ascribe meaning to things to try to answer this “why,” but are inevitably frustrated. We are all just like Sisyphus endlessly pushing his rock, only to have it roll back down.

Camus identifies two means of escape from this absurd condition. One is physical suicide, which frustrates the absurdity of life by refusing subjection to it. The more common response is what Camus dubs “philosophical suicide.” Kierkegaard’s religious “leap of faith” is one example. But he also condemns the rationalism of Aristotle, Aquinas, and Descartes, stating that rationalism itself operates with a presupposition of the universe being rational – another leap of faith. Camus contends that both forms of suicide are an irrational imposition onto the experience of life. The only proper response to reality is to accept it for what it is, and live in it. “The struggle itself towards the heights is enough to fill a man’s heart. One must imagine Sisyphus happy.” We ought to just push our boulders and enjoy the joy, mundanity, and the suffering; there’s plenty of time for being dead later.

His other major philosophical essay was The Rebel. Camus was an intensely convicted man, and could not stand injustice. However, he thought the proper way to deal with injustice was rebellion, not revolution. Rebellion, to Camus, was a spontaneous response to a particular injustice. Revolution was an attempt to upend the system and replace it with a new one. Camus points out that the only way to replace an entire system is through use of oppression, which defeats the purpose of upending the old system in the first place. He uses the example of the French Revolution’s rapid descent into mass murder, as well as the Soviet gulags (despite being a communist).

This comparison did not sit well with Sartre, who was a major supporter of the USSR. Criticisms went back and forth between the two. Camus (rightly) suggested that Sartre’s ivory tower intellectualism disconnected him from real suffering and the plight of real people. “People are now planting bombs on the tramways of Algiers. My mother might be on one of those tramways. If that is justice, I prefer my mother.” Sartre called Camus a moralistic little crook from Algiers. His dismissal of Camus on the grounds that he came from a lower class background sort of proved Camus’ point. Shouldn’t a Marxist consider the lower classes his equals?

But don’t take my praise for Camus in this one instance as a moral lionization. He drove the mother of his children to attempt suicide with emotional neglect and serial adultery. And he was unapologetic about it. “It is an error,” Camus wrote, “to make Don Juan an immoralist: in this respect he is like everyone else. He has the moral code of his sympathies and his antipathies.” Apparently his wife’s suicide wasn’t as big a deal as philosophical suicide.

Conclusion

Existentialism is an umbrella of post-enlightenment belief systems. The core doctrine is that existence precedes essence; the color comes from what to do about that fact. Existentialism is the natural and unavoidable corollary to atheism or agnosticism – the ideas that God does not exist, or practically doesn’t exist.

My critique of existentialism will focus on the fact that it is modally unjustifiable. You can follow the hyperlink here or navigate to the critique using the menu.