Definition

Existentialism is not a religion, but a belief system, the central dogma of which is the nonreality of essence. That is, the claim that “essence” is merely an imposition made by the mind. No one is here “for” something, no one is required to be a particular way, life is what you make of it. Although Sartre’s “existence precedes essence” carries some implied philosophical baggage beyond this, I think it is a pithy description of this idea. I will argue that existentialism is concomitant to atheism and agnosticism, discuss certain commitments this creates for atheists and agnostics, and then will attack the probability of their positions by proving these commitments untenable.

YouTube video presentation of this argument here.

Preface: Existentialism

Before we move forward, we have to understand the meaning of the word essence. Essence is “that which is expressed by its definition,” or, more concretely, “the basis by which nature is expressed.” So, for example, the “essence” of a guitar would be “to be a stringed musical instrument, with a fretted fingerboard, and six or twelve strings played by plucking or strumming.” If something expresses that essence, it is a guitar. If something does not express that essence, it is not a guitar.

So to say that existence precedes essence is to say that the idea of essence is subjectively imposed, as opposed to objectively instantiated. That is, a policeman is really just a uniformed person who is allowed to handcuff people. The president is really a person in a suit who bombs things with impunity. Even inanimate things like chairs are really only chairs because we define that pile of atoms as such, not because they have an essential, objective “chair-ness.”

Now Sartre extrapolates further on the idea by saying that “if existence precedes essence, God is meaningless.” I would go even further. If existentialism is true, God can’t exist. God is a pure essence, not a material being, and that can’t be real under this paradigm.

Preface: Essentialism

But on the other hand, if essences are objective, then God certainly exists. We can deduce this as follows:

Given that essences exist, we see that some are distinct from their existence. That is, they exist, but easily might not have. How do we account for this? Well, nothing can create itself, for that would require existing before one exists, a contradiction. But not every essence can rely on another for existence, for this would result in an infinite regress of beings passing along a property none of them have – imagine plugging a TV into an infinite chain of power strips; it would never turn on. Thus, one essence must be identical to existence. That is, it is existence – it is not self-created, but self-evident, uncreated. There can only be one such being, since any distinction from this essence would be a distinction from pure existence, which is the exact sort of thing which requires pure existence to precede it. Let us call this being “To Be.”

To Be cannot change, since it cannot be distinct from its essence, and so To Be is immutable. But what is immutable must also be eternal, since going from nonexistence to existence would constitute change. But what is eternal cannot be material, since materiality is inherently subject to the limitations of space and time. Further, To Be cannot be composed of parts, because a composite being’s existence is dependent upon its parts, and this being depends on nothing. So, it must be absolutely simple. This being is the principle by which all things exist, and is in this sense present to all beings. But because To Be is simple, it is wholly present to all things, whether the smallest particle or the entire universe, and present to its whole self. So, To Be is omnipresent.

Power is the ability to act upon something else. An agent’s power is greater the more it has of the form by which it acts. For example, the hotter a thing, the greater its power to give heat; if it had infinite heat, it would have infinite power to give heat. This being necessarily acts through its own essence, since nothing precedes its essence. But it is one with its essence, and since its essence is infinite, its power must be infinite. So it is omnipotent. But an immaterial, immutable being’s power cannot be physical. Rather, its power must be power of mind, which can change reality without itself changing, as one unchanging idea of ice cream may cause your physical body to desire and retrieve ice cream. Because this being is immutable, simple, eternal, immaterial, and wholly present to all things, it is thus omniscient. Its knowledge is reality.

So, To Be is eternal, omnipotent, omnipresent, and omniscient. God.

Metaphysical Argumentation

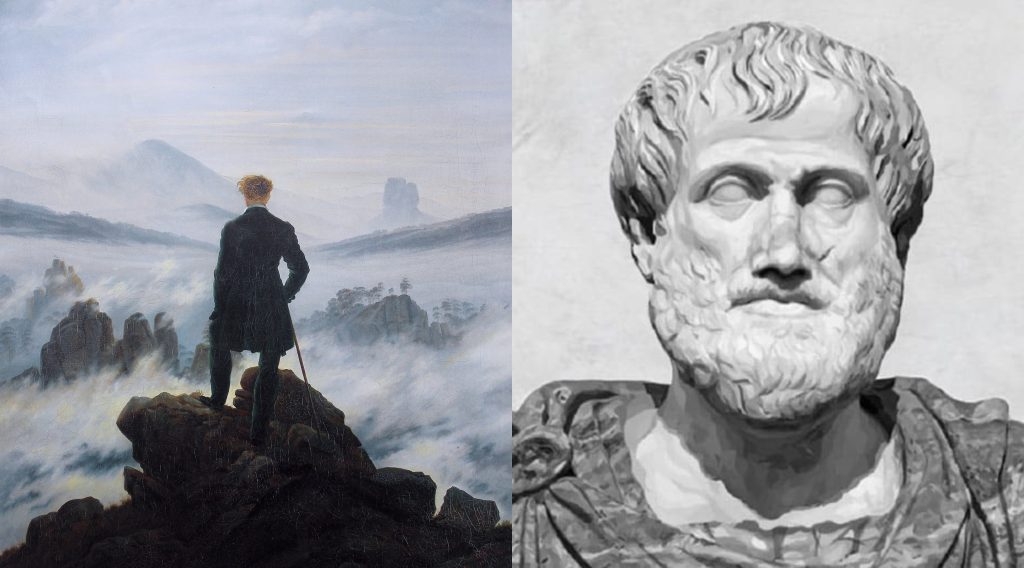

As such, we find ourselves with two options; two paradigmatically opposed universes. In Sartre’s existentialist universe, there is no objective essence. God cannot exist. In Aristotle’s essentialist universe, everything has an objective essence. God must exist. Now, these two ideas are metaphysical. That is, they describe a “foundation” of reality; they are prior to empirical evidence. So, I can’t put a chair under a microscope and find its essence, for example. But just because metaphysical claims are untestable does not mean they are unreliable or ignorable. Everyone believes in some metaphysical paradigm, and all empirical claims rely on metaphysical claims preceding them. You can’t use the scientific method without first believing in the untestable law of noncontradiction, for example.

How, then, are we to decide between one metaphysical paradigm and another? Suppose I presented the following metaphysical dichotomy: you either are you, or you are not you. Which are you to believe? While you cannot “test” whether you are you, it is clearly the intuitive conclusion, and the alternative leads to apparent absurdities. As such, you can safely conclude that you are, in fact, you. Here, we likewise have two possible metaphysical realities: either there is essence, or there is not. Which are we to believe? I will argue that essentialism is clearly the intuitive conclusion, whereas existentialism leads to absurdities. Given this, we ought to believe essentialism, reject existentialism and consequently atheism and agnosticism.

Essence

In Existentialism is a Humanism, Sartre produces a pithy, biting syllogism. “If God exists, I cannot be free. But I am free. Therefore, God does not exist.” His provocative conjecture is meant to describe the immense freedom consciousness implies. Sartre believed that the mind does not have a fixed identity the way the body, or a rock, or a chair does. It is malleable, it can consider anything it wants; it has no thing-ness. Sartre’s syllogism means to point out that because the mind has no thing-ness, man has no thing-ness, and therefore no essence. And if man has no essence, then his existence precedes his essence. Unlike a chair, which exists first as an idea in someone’s mind and then as a fixed object, you can shape your own identity through your own mind. God does not determine man; rather, man determines himself.

In De Anima iii, Aristotle has his own discussion of the no thing-ness of the mind. He points out that the mind is “in a sense all things” – like Sartre, he believes in the mind’s total malleability, its capability to consider anything. However, this observation led Aristotle to the exact opposite conclusion. To Aristotle, the human mind’s no thing-ness is its essence – that is, its essence is to receive the essences of things outside itself and know them through its total malleability. But this means man does have an essence: “to be an animal with the power to understand essence.” Further, it means that essence is something objective which we receive from reality, not something subjective which we impose upon reality. A frog really is a frog, not just a collection of atoms we categorize as a frog.

So, a priori, either of these could be true. But which is worth assuming?

When it comes to our sense experiences, we assume that a sense perceives something as it is in reality. When we see something, unless there’s a serious malfunction, we see it because it’s actually there. Likewise with the other senses. We do not assume that when we touch a coarse material, our imagination imposes the feeling of coarseness upon our hand; rather, we receive the real coarseness. But our relationship with essence is just as fundamental, just as effortless. Stop reading this – look around and try as hard as you can not to see essences in everything around you. I admit that for a short time you can almost “hide” the essence of something from yourself, maybe by staring at it for so long that it starts to look strange. But I would equate this to, say, wearing a ring for so long you forget it’s there.

Could it be that we just impose concepts upon things very naturally? Look around the room again, and this time apply names to everything you see. This takes a moment of thought, does it not? So we see that applying a nominal idea foreign to the essence of an object takes effort. Merely seeing essence, on the other hand, is as natural and inescapable as feeling an object when you touch it.

Perhaps evolution has developed in mankind some sort of broad, innate heuristic grouping mechanism? No; this is impossible – evolution adapts a genome to a material environment, while humans innately experience essences which transcend material correlates. For example, Chopin’s Nocturne op. 9 no. 2, Van Gogh’s Starry Night, and Percy Shelley’s Ozymandias have absolutely nothing material in common, yet each demonstrates beauty to the human mind. The sentencing of Adolf Eichmann, the passage of the 13th amendment, and a son giving his beloved father a eulogy are each examples of justice. Neil Armstrong’s first steps on the moon, Desmond Doss rescuing 75 soldiers without firing a shot, and President Reagan’s demand that the USSR tear down the Berlin Wall are all examples of courage. None of these deeply moving events share any sensible similarities. How could a genome develop innate heuristics for concepts with no referent in material reality?

To reiterate, our experience of essence is just as fundamental and effortless as our experiences of sense. Conversely, we know that imposing nominal concepts onto things, like names, is not an effortless task. This suggests that we receive essences, as we receive sense data. Furthermore, the vision of essence can’t be some evolutionary development, as it deals with universal categories which transcend material aspects. As such, it seems we ought to believe that essence is real and objective.

Purpose

If the existentialist position is correct, then purpose is a subjective imposition from the mind of an agent. But if the conscious agent is the arbiter, how does he determine purpose? Purpose is often cited as a creative project, a fun job, time with family, political power, or something like those. But if there is no coherent, objective structure to reality, then even those desires are shaped arbitrarily by biology, society, or religion. This introduces man into an impossible situation. One does indeed have the power to nominally assign purpose to one thing or another, but all the sources which shape his choice are themselves arbitrary and meaningless. A man can do what he desires, but if his desires come from meaningless preconditions, then they too are meaningless. So, under the existentialist paradigm, there is no real purpose.

Aristotle has a different response. He taught that all things have a purpose (“final cause”) determined by their essence. So, for example, God’s purpose as the greatest good is contemplating Himself (since, being the greatest good, any other exercise would be beneath Him), man’s purpose as a rational animal is to live according to reason (also known as virtue), a fox’s purpose is to do fox things as best as possible, a planet’s purpose is to perform revolutions, and so on. A thing better fulfills its purpose the more perfectly it does whatever it does, as a golfer who hits 18 holes-in-one is greater than one who hits par. In this way, Aristotle says, all things ultimately aspire towards God, who is perfection itself, according to the limitations of their essences.

So again, we have a dichotomy, and either option could be true a priori. On the existentialist side, nothing can have real meaning. All the things we derive meaning from are themselves meaningless. On the essentialist side, everything has real meaning. All things tend towards God’s perfection in whatever mode is appropriate, and for man this is pursuing the life of perfect virtue he explores in Nicomachean Ethics. Which is worth assuming?

We are rational creatures, which means we will the end before the means. This means some purpose is required for our actions to be coherent. We are not foxes or gorillas, compelled by nature to act without deliberation. But this means we must have one end which all other ends serve. If this ultimate end is meaningless, arbitrary, and liable to be change, then so is everything in service of it. Without an ultimate “why,” we descend into a nihilistic hole where everything is useless and there’s no subsisting reason to do anything. If life is just a cosmic accident, it makes no difference whether I have a cup of coffee or whether I kill myself.

With the general abandonment of religion, and thus ultimate purpose, people have begun to see themselves as psychological creatures instead of spiritual creatures with spiritual purpose. They posit that we are governed by impersonal subconscious influences, not virtue. If there is no God and no soul, what guides us beyond our physical brains and appetitive desires, after all? We can see the practical results of this type of thinking all around us. Each successive generation reports greater feelings of hopelessness. Objective markers of well-being are increasing, and instead of depression decreasing, it is increasing at the same rate. Compare this to Holocaust survivor Viktor Frankl’s experience in the concentration camp, where those who had purpose managed to thrive, even in the midst of a death camp. “In some way,” he said, “suffering ceases to be suffering at the moment it finds a meaning, such as the meaning of a sacrifice.”

We observe that all the creatures around us are structured for life in their given environments. That is, reality has molded them into an appropriate shape. We also observe that human beings require purpose (and therefore God), both logically and practically. People with purpose can handle anything. People without purpose can’t even handle being comfortable. So, to say that purpose is imaginary is to assert that reality fashioned man – and seemingly only man – to have a fundamental need for something which doesn’t exist. That man is the one species whose proper function normatively results in irrational behavior, existential dread, and hopelessness. If hunger is evidence for the existence of food, is our hunger for purpose not evidence of its existence?

Morality

This preface follows much the same logic as the previous section’s preface. Recall my initial point on purposelessness – if every precondition of your worldview is meaningless and arbitrary, then your worldview is meaningless and arbitrary, and you can’t create purpose. Likewise, though an existentialist may hold to certain personal moral beliefs, they cannot propose an objective, universally binding moral law, since any source they would appeal to in an attempt to justify their values – biology, social cohesion, consequences – would itself be an arbitrarily selected metric.

Contrarily, recall my second point on purposefulness – if all things have purpose (to tend toward God), then everything is meaningful. This means that morality is willfully acting in accord with one’s essence and tending towards perfection. What is evil under this paradigm? It is acting contrary to one’s essence and tending towards imperfection. It is not the consequence of the act which makes it wrong, it is the nature of the act. This is called natural law theory, and it treats morality like physics or biology: a coherent set of objective laws found in reality. We may disagree on these values (much like we often disagree about scientific theories), but they’re really there; they aren’t subjectively imagined, but imposed upon reality by God’s very nature as the absolute, invariant, universal standard of goodness and justice. God neither invents nor conforms to the moral order; He is the moral order.

So, we find ourselves at our third dichotomy, and once again, either option could be true. On the existentialist side, morality cannot be objective and universally binding. On the essentialist side, moral laws are just as objective and universally binding as the laws of physics. Which is worth assuming?

There are two glaring issues with the existentialist position. First, the imposition problem. One may appeal to certain axioms to develop a moral system – common examples include “avoid causing needless suffering,” “produce the greatest good for the greatest number,” and “treat rational beings as ends, not as means.” Although one can derive objective conclusions from these axioms once imposed, their imposition is nonetheless arbitrary. An atheist virtue ethicist may be bound to avoid drunkenness, but nothing binds him to virtue ethics. If he really wants to, he can easily just switch to consequentialist reasoning (“as long as I don’t hurt anybody”) and do as he pleases. But this means the moral law doesn’t actually exist at all, just a series of nominal principles one may or may not appeal to. As Ivan says in Dostoevsky’s masterwork, Brothers Karamazov, “if God does not exist, then everything is permitted.”

Even if one were personally morally consistent, they have no basis by which to impose their subjective system on anyone else as objective truth. But this would mean things like child molestation or genocide aren’t actually wrong, just social faux pas. Though the majority can certainly agree to throw pederasts in prison for the subjective good of society, they couldn’t say that pederasty is objectively morally evil, much like we can certainly put down a rabid dog for the good of society, but can’t call the fact that it bit someone objectively morally evil. One might try to argue that certain moral facts (like the wrongness of molestation) are just necessary truths (the way A<A+1 is a necessary truth), but even if this were so, why would we anticipate that a mindless, meaningless, survival-oriented process of evolution would give us the ability to access such truths?

Second, even if one were to deny all this and claim that moral axioms are necessary truths and that we can somehow justify the belief that we can access them, moral systems which depart from a supernaturally grounded natural law lead to madness. For example, we can follow all three of the humanistic moral dicta I listed previously and come to the conclusion that having sex with animals is morally permissible. It’s not like we ask them for consent before we kill them for food, and they certainly aren’t rational, so what’s the difference? We can likewise conclude that it is morally permissible to painlessly euthanize a dog and have sex with its corpse, to abort an infant post-birth but pre-consciousness, for two twin brothers to get married, to eat a braindead orphaned child, or to use a consensually obtained corpse as a sex doll.

Now, all of these would be wrong if humans have intrinsic dignity and sex is sacred. But that’s the sort of thing the theistic natural law ethicist can claim, not the existentialist. And this is precisely the issue. Everyone has deep intuitions that the activities listed previously are monstrous. But if existentialism is true, and existentialism is consistent with these values, why is that the case? If existentialism were true, wouldn’t it make more sense if we were to neutrally accept the permissibility of braindead orphan baby cannibalism the same way we just neutrally accept that the sky is blue? Why is it that, regardless of stated beliefs, we have unshakeable intuitions that human life and sex are sacred? And if you find it impossible to reject these intuitions, how can you hold to a system which does?

Conclusion

There are two metaphysical views of reality I have discussed; one must be true, and the other must be false. In the first, the universe of the existentialists, there is no such thing as essence, purpose, nor objective morality. In the second, the universe of the essentialists, God exists and is responsible for the structure and order of reality. The lynchpin of this order is essence. Essence defines purpose, and purpose defines moral values. In each case, the existentialist opinion does violence to a fundamental intuition inseparable from the human experience.

First, we assume that all of our sense experiences are dependent on something in reality giving rise to them. Like sense experience, the essences of objects come to us effortlessly. This is unlike verifiably nominal concepts, such as names, which require effort to “see in” things. It is absurd to posit that this is a result of evolutionary mechanisms, because we can effortlessly recognize essences which share no material correlates. For example, music, paintings, and poems all evoke a sense of beauty. How could a genome measure these things and unify them under one heuristic?

Second, we see that reality molds creatures to fit their environments. But without purpose, human behavior is logically incoherent, and men can hardly stand to live at all. There is no reason to assume reality would craft an innately incoherent creature. It would be absurd to assume that men who thrived in concentration camps have a weaker grasp on reality than those who can’t even handle satiety. Just as hunger suggests food exists, man’s longing for purpose suggests purpose exists.

Third, we see that morality is either an objective corollary to essence, or else is simply opinion. We know the human conscience is deeply concerned with moral value judgments. But the existentialist has no means by which to surely determine nor impose a moral system. Further, even if they claimed to have such a thing, humanistic systems lead to unacceptable moral conclusions. But if a system leads to unacceptable conclusions, then we must reject that system. Consequently, unless you believe it is ethical to use a braindead orphaned baby for food, you shouldn’t be an existentialist.

Now, this argument took on existentialism on its own metaphysical terms in order to demonstrate its absurdity and untenability as a belief system. Anything which would commit one to this belief system – namely, atheism and agnosticism – should be rejected. Though this props up theism by process of elimination, this is certainly not the only reason to be a theist. You can read my cosmological argument here, my argument from consciousnesses here, and my response to common arguments for atheism here. So, not only is theism the superior metaphysical assumption, it has significant concrete evidence to support itself. The question is not whether God exists, it is which religion is true. I address this question over the next six articles.